A man rapes and murders a woman in the most gruesome fashion. Is he responsible for what he has done? He had a bad childhood, and a bad stomach because he had too much spinach. Furthermore, a pigeon built a nest in his braincase, which impaired his emotional regulation. Can we blame him for his crime, or was he merely the victim of unfortunate circumstances?

Stories like these, which sound contrived but are probably true, form the basis on which Sam Harris argues against the idea that humans possess free will. I did not chose to write about Harris’ essay, I was compelled by the external world and by unconscious processes in my brain. Specifically, I would have never read this tedious pamphlet, had not a good friend recommended it to me. And he did not recommended it out of his own volition either, somehow his nerdy mind caught onto this topic and forced him to tell me about it.

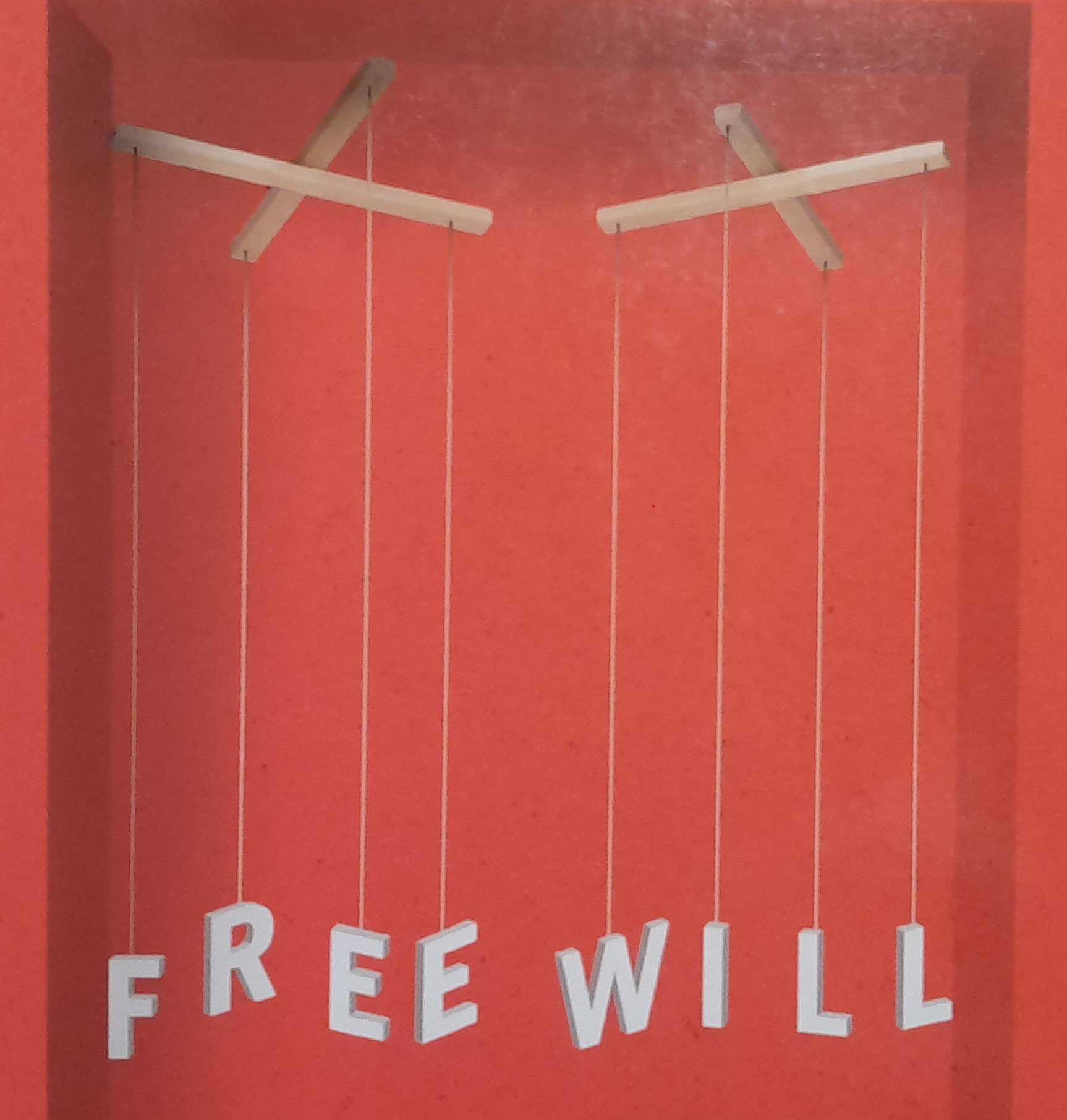

You see where this is going. Unlike Harris in his essay Free Will, I will spare you any more of this type of reasoning. Harris finds eloquent words and many odd examples to make his point, but there really is not much more to it. Free will doesn’t exist, because we don’t control the neurons in our brain which cause us to adopt a certain behaviour, though it feels like we made the choice ourselves.

Even Sam Harris would not be able to stretch that little content across more than 60 pages, so he considers the implications of recognising that free will is an illusion. They are not impressive. In daily life, we are served best if we act as if free will existed, as this might compel us to take actions to better our lot. Of course, if free will really doesn’t exist, this recognition is also pre-determined, and which stance we take has been decided before we thought about it.

The moral implications might be more consequential, albeit not new. Harris argues that we should reconsider our views on criminals - they are victims of their circumstances, we should not hate them, but rather cure them. Or, if their viciousness cannot be erased, we ought to contain them to protect ourselves. This echoes what Nietzsche predicted on how a future society will treat criminals. Yet, there may be room for punishment, if this helps deterring potential offenders. To my surprise, Harris also admits that punishment may be a worthwhile course of action if it makes the relatives of the victims feel better. I would add that the illusion of your enemy being personally responsible may instill in you a hatred that drives you to vanquish him, and thus triumph. A meek, understanding attitude may well precipitate your downfall.

In summary, the realisation that free will does not exist changes little. I will continue to act as if it did, and so should you. All that is left for me is to curse the demon that has arranged the atoms of the universe in such a way that I was compelled to read Free Will - I would have chosen to not do so, had I had free will.